Hospital capacity challenges pre-date the pandemic: Solutions series, part II

This is the second part of a series examining the policy barriers and solutions to reducing surgical wait times in Canada. The series has been adapted from a research paper by Andrew Longhurst. The complete paper with reference list for the footnotes is available here.

The problem with the ongoing strain of COVID-19 on hospitals is compounded by the fact that Canada has some of fewest acute care beds per capita compared to other OECD countries, and a lack of publicly funded home and community care services, especially for seniors. Critically, this is not just a matter of physical space – but having the necessary workforce needed to staff acute care beds.

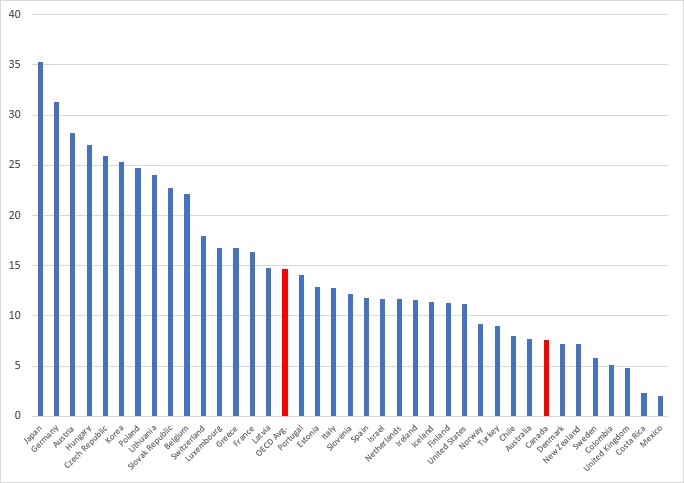

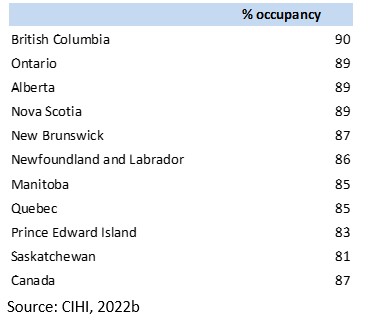

Canada ranks 31 out of 38 OECD countries when it comes to acute care beds per population (Figure 2). At 7.7 acute beds per 1,000 people, we are significantly below the OECD average of 14.7 beds per 1,000 people.[1] Canada’s ranking at the bottom among of OECD countries for beds per capita would not necessarily be so problematic if hospitals could maintain lower occupancy rates and efficient patient flow. However, medium and large hospitals had an average occupancy rate of 88 per cent in 2019/20 (Table 4).[2]

Occupancy rates below 85-90 per cent are recommended for maintaining patient flow, wait times, and patient safety.[3] When occupancy rates are near 100 per cent, hospital overcrowding can impact working conditions and the quality of patient care, making infection control more difficult.[4] A systematic review found that in nine out of 12 studies, “bed occupancy rates and understaffing directly influence the incidence of hospital-acquired infections.”[5] And a Canadian study also concluded that increased hospital occupancy is “strongly associated with emergency department length of stay for admitted patients, [and that] increasing hospital bed availability might reduce emergency department overcrowding.”[6]

Figure 2: Acute (curative) care beds per 1,000 in OECD countries, 2020 or latest available

Source: OECD, 2022a

Table 4: Occupancy rates, large, medium, and teaching hospitals, 2019/20

Overcrowding and bed shortages were common before the pandemic. In Ontario, a 2020 CBC investigation found that 83 hospitals were operating beyond 100 per cent capacity for more than 30 days, 39 hospitals hit 120 per cent capacity or higher for at least one day, and 40 hospitals averaged 100 per cent capacity or higher.[7] When hospitals are overcapacity this results in “hallway medicine” where patients remain in emergency departments because all staffed inpatient beds are occupied. Again, staffing is most often the limiting factor. In many cases, hospitals have the physical beds, but do not have required staff.

The pandemic has placed additional and unprecedented strain on hospitals and workforce, resulting in cancelled scheduled care, including surgeries and diagnostic testing. However, these capacity challenges are compounded by the number of seniors who are unable to access publicly funded seniors’ home and community care.

Constrained access to seniors’ home and community care

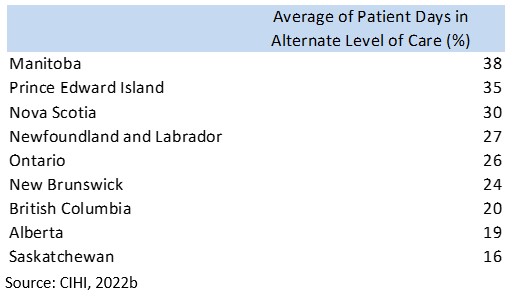

Declining access to publicly funded seniors’ home and community care contributes to surgical wait times. This issue – referred to as alternate level of care (ALC) – is symptomatic of a fragmented, underfunded, and privatized seniors’ care system. ALC refers to patients who cannot be discharged from hospital because beds or appropriate supports in the community are not available, including long-term care, assisted living, supportive housing, or independent living with home support.

The lack of available home and community care means that patients, often seniors with complex care needs, remain in hospital as ALC patients because they cannot be discharged. In 2020/21, an average of 24 per cent of patient hospital days in Canada were ALC days, including 26 per cent in Ontario, 20 per cent in BC, and 38 per cent in Manitoba (Table 5). This means that nearly one-fourth of all the patient care provided in hospitals (measured as patient days) was the result of patients who could not be safely discharged and supported in more appropriate home or community settings.

A more detailed look at home and long-term care access reveals a dire situation. Statistics Canada’s Canadian Community Health Survey, found that in 2015/16, over one-third (35.4%) of people with home care needs (approximately 433,000 people) did not have those needs met.[8] Unmet needs were more prevalent among those who required home support (i.e., non-medical personal assistance) compared to health care needs (i.e., professional health services). Availability was most often the barrier to obtaining home care services, especially for those with unmet professional health care needs. Lower income individuals without private insurance were more likely to have unmet care needs, showing the importance of publicly funded home care.

Unfortunately, there is a data gap in understanding the current situation in Canada. Data on Canada’s long-term care spaces are no longer collected by Statistics Canada or CIHI.[9] However, media accounts and research reports have documented declining access in many provinces, including BC and Alberta.[10]

[1] OECD, 2022a.

[2] Occupancy rates are calculated as the number of beds occupied divided by the number of beds available, multiplied by 365 days. Pre-pandemic occupancy rates are used since many health authorities cancelled scheduled care in order to free hospital beds and staffing resources. Thus, hospital occupancy rates for 2020/21 have not been used.

[3] Bagust et al., 1999; Forster et al., 2003.

[4] Kaier et al., 2012.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Forster et al., 2003.

[7] Crawley, 2020.

[8] Gilmour, 2018, p. 8.

[9] Statistics Canada’s Long-Term Care Facilities Survey was terminated following the 2014 survey.

[10] McGregor and Ronald, 2011, p. 10; Campanella, 2016; Longhurst, 2017.