Reducing surgical wait times: Solutions series, part I

This is the first part of a series examining the policy barriers and solutions to reducing surgical wait times in Canada. The series has been adapted from a research paper by Andrew Longhurst. The complete paper with reference list for the footnotes is available here.

Since March 2020, thousands of scheduled surgeries have been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of these procedures have since been completed, but wait times continue to deteriorate. While long wait times are not a new challenge, the unprecedented pressures on health systems are amplifying longstanding problems. The federal and provincial governments have negotiated a 10-year funding deal at the same time as many provinces are pursuing greater for-profit involvement in the delivery of surgeries and diagnostics.

Yet, the weight of the research tells us that privatization does not solve public wait time challenges. More than two decades of research and experience tells us that Canada requires much greater federal and provincial leadership to reduce wait times through evidence-based strategies. In fact, outsourcing publicly funded procedures creates barriers to implementing and sustaining necessary public improvements, and encouraging private payment widens inequities in health care access based on ability to pay, not medical need.

Instead of privatization, federal and provincial governments should move expeditiously on long-stalled policy strategies to make much smarter use of our public health care system in order to reduce wait times. This will require federal and provincial governments to take a coordinated approach to redesigning how surgical services are delivered.

The case for dramatic public system improvement is more urgent than ever. Since the early 2000s, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) began documenting the efforts of local groups of surgeons and health system administrators to implement promising initiatives such as operating room efficiencies and team-based care models. In 2016, the CCPA assessed the state of successful and promising initiatives in BC, only to find that many were downgraded or discontinued due to a lack of health authority and provincial government leadership to make these improvements standard practice provincially.[1] The story is similar in other provinces: there are pockets of promising public innovation, but a lack of federal and provincial leadership to expand these practices across provincial health systems.

Canada’s ability to manage and reduce wait times amidst major health system disruptions, such as COVID-19, depend on putting research evidence and policy learning into practice. This series provides a framework of evidence-based policy strategies that will be necessary to manage and reduce public surgical wait times over the long term.

Why surgical wait times remain a persistent policy challenge

Over the last ten years, Canada has had mixed success in reducing surgical wait times. In the early 2000s, the federal government provided significant policy leadership and funding to provincial governments. Important progress was made since that time, but provinces continue to struggle with sustaining wait time improvements over the long term. This is largely due to a focus on short-term injections of funding with no requirements that provinces implement system improvements.

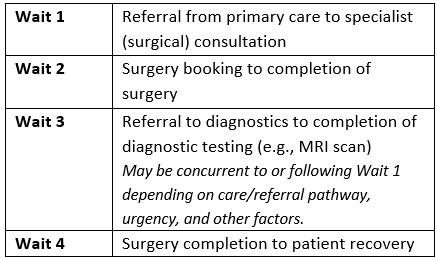

Since the early 2000s, provinces have greatly improved their wait time data collection and public reporting. However, pan-Canadian data are only available for the four “priority procedures” contained in Table 2. These data, publicly reported by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), reflect Wait 2 (time from surgery booking to surgery completion, see Table 1), and therefore underestimate the entire patient journey from primary care referral to surgery completion. Diagnostic imaging wait time data is not available for all provinces, and pan-Canadian benchmarks have not yet been established.

Table 1: Wait times for surgical patients

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, nearly 560,000 fewer surgeries were performed over the first 16 months of the pandemic alone compared with 2019.[2] This has created a significant backlog of surgeries in provinces at a time when the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the removal of public health measures is severely straining hospital capacity and the health workforce.

In the first wave, many surgeries were postponed in order to preemptively free hospital resources for a surge in COVID-19 patients requiring inpatient beds.[3] And subsequent waves have resulted in postponed surgeries as hospitals struggle to maintain scheduled services while caring for COVID-19 patients and facing acute staffing shortages due to absences and burnout.

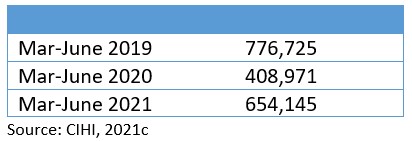

Overall, provinces have made significant improvements reducing wait times since 2020.[4] However, the significant reduction in total surgeries completed in 2019 (pre-pandemic) compared to the same period in 2020 and 2021 indicates that provinces are still working down surgical backlogs, and that newly-diagnosed patients who require surgery may wait longer because of this backlog. Even so, it is a testament to health care providers and our public health care system that provinces have been able to increase surgical volumes within roughly 85 per cent of pre-pandemic levels (Table 2).

Table 2: Total surgeries completed during pre-pandemic and pandemic periods in Canada

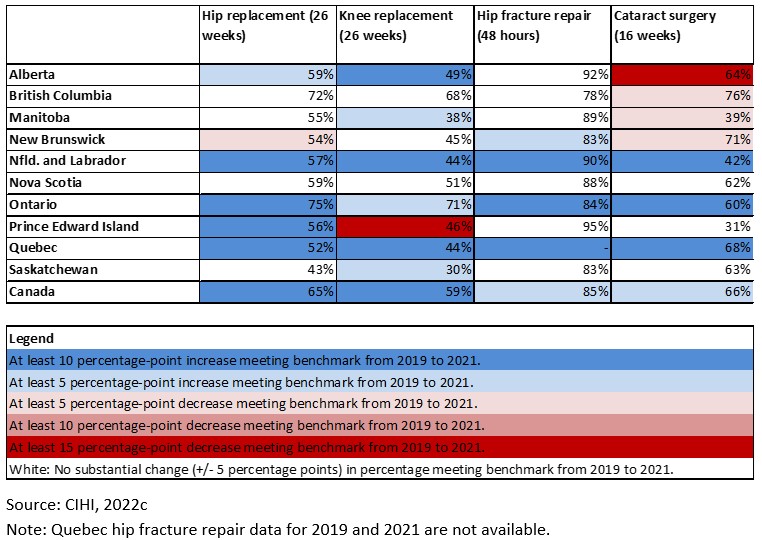

As shown in Table 3, the majority of patients in Canada received priority procedures within the Wait 2 benchmark in 2021:

- For hip replacements, 65 per cent of patients, received surgery within the 26-weeks benchmark.

- For knee replacements, 59 per cent of patients received surgery within the 26-weeks benchmark.

- For hip fracture repair, 85 per cent of patients received surgery within the 48-hours benchmark.

- For cataract surgery, 66 per cent of patients received surgery within the 16-weeks benchmark.

Table 3: Percentage of patients receiving surgery within benchmark, 2021

And while provinces have generally made significant strides increasing surgical volumes and working down backlogs, provinces have had mixed successful over the last three decades reducing and sustaining wait time improvements. The policy strategies to overcome this persistent challenge is the focus of this series.

[1] Longhurst et al., 2016.

[2] CIHI, 2021b.

[3] Trevithick, 2020.

[4] CIHI, 2021b.